One day in 1656, the citizens of Magdeburg, Germany were startled by the appearance of strange unidentified flying objects hovering over their town. Documented by a now-famous contemporary engraving, it should have led to panic in the streets. The town's mayor, however, Otto von Guericke (1602-1686), calmed the crowd with confidence empty of any reassurance whatsoever: Nothing to worry about, it's nothing at all. Nothing's happening. You are seeing nothing in action.

It was a great day for nihilism.

What the good folks of Magdeburg actually saw were two teams of eight horses try to pull apart two 20-inch diameter copper hemispheres that were greased at their mating rims and sealed when all the air was pumped out. It couldn't be done. Guericke had dramatically demonstrated the existence of a vacuum, of nothingness within the sealed hemispheres. In short, he proved that nothing could exist within something.

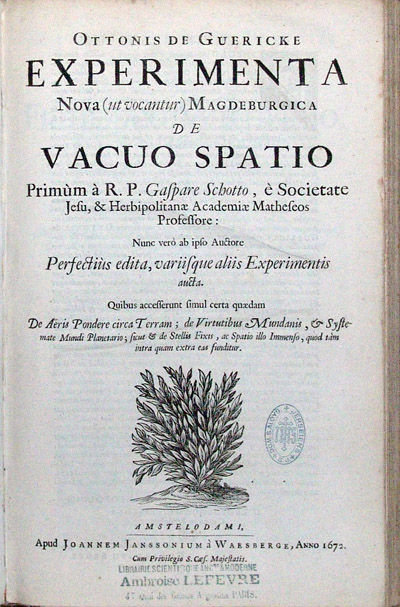

This was major. It was also controversial. The results are found in Guericks's Experimenta nova (1672), one of the great classics of science.

The subject of a vacuum or void, that is, nothingness, vexed natural philosophers and theologians. Ecclesiastic Jacques du Bois and Jesuit scholars Athanasius Kircher and his assistant and protégé, Gaspar Schott were in the middle of it along with Guericke, a scientist and inventor as well as politician.

"Schott first published what had originally been intended as a brief guide to the hydraulic and pneumatic instruments in Kircher's Roman museum, expanding it into the first version of his Mechanica hydraulico-pneumatica [1658]. But he added as an appendix [pp. 441-488] a detailed account of Guericke's experiments on vacuums, the earliest published report of this work. This supplement contributed greatly to the success of Schott's compendium; and as a result he became the center of a network of correspondence as other Jesuits, as well as lay experimenters and mechanicians, wrote to inform him of their inventions and discoveries. Schott exchanged several letters with Guericke, seeking to draw him out by suggesting new problems, and published his later investigations" (DSB).

It was a great day for nihilism.

What the good folks of Magdeburg actually saw were two teams of eight horses try to pull apart two 20-inch diameter copper hemispheres that were greased at their mating rims and sealed when all the air was pumped out. It couldn't be done. Guericke had dramatically demonstrated the existence of a vacuum, of nothingness within the sealed hemispheres. In short, he proved that nothing could exist within something.

This was major. It was also controversial. The results are found in Guericks's Experimenta nova (1672), one of the great classics of science.

The subject of a vacuum or void, that is, nothingness, vexed natural philosophers and theologians. Ecclesiastic Jacques du Bois and Jesuit scholars Athanasius Kircher and his assistant and protégé, Gaspar Schott were in the middle of it along with Guericke, a scientist and inventor as well as politician.

"Schott first published what had originally been intended as a brief guide to the hydraulic and pneumatic instruments in Kircher's Roman museum, expanding it into the first version of his Mechanica hydraulico-pneumatica [1658]. But he added as an appendix [pp. 441-488] a detailed account of Guericke's experiments on vacuums, the earliest published report of this work. This supplement contributed greatly to the success of Schott's compendium; and as a result he became the center of a network of correspondence as other Jesuits, as well as lay experimenters and mechanicians, wrote to inform him of their inventions and discoveries. Schott exchanged several letters with Guericke, seeking to draw him out by suggesting new problems, and published his later investigations" (DSB).

Schott, who Guericke cites in the subtitle to Experimenta nova, was a supporter of Guericke. His mentor, Kircher was not; a vacuum is impossible: God fills everything. This is one of the few examples of Kircher and Schott in disagreement.

|

| Engraved titlepage. |

"Is it God's immensity or is it independent of God…Guericke's position on this matter emerges in the course of a summary account [in Experimenta nova] of the opinions of the ecclesiastics Jacques de Bois of Leyden and Athanasius Kircher, the eminent Jesuit scholar. In his Dialogus Theologicus-Astronomicus, published in 1653 and directed against Galileo and all his defenders of the heliocentric cosmology, Jacques du Bois had proclaimed the infinite omnipresence of God in an infinite void beyond the world. Du Bois should not have placed the divine essence in an infinite void, complained Guericke, but ought rather to to have declared that ' there is a place or space not in which the divine essence is, but which is itself the divine essence..."

"…[Guericke's] criticism of Kircher differed somewhat…Kircher believed that even if a void culled exist without a body, which he denied, it could not exist without God. In the passage cited by Guericke, Kircher explained that 'when you imagine this imaginary space beyond the world, do not imagine it as nothing, but conceive it as a fullness of the Divine Substance extended into infinity.' In Guericke's judgment, Kircher was wrong to say that 'God fills all imaginary space, vacuum or emptiness by His substance and presence' and simultaneously deny the existence of empty space. 'For how can God fill what is not' [Experimenta nova, p. 64]. Rather, Kircher ought to have concluded with Lessius that 'imaginary space, vacuum, or the Nothing beyond the world, is God himself,' as he finally does when he announces that the space beyond the world is not Nothing, but is the fullness of Divine Substance.'

"But if space is God's immensity, or even God Himself, Guericke insisted that we must nevertheless understand that 'the infinite essence of God is not contained in space, or vacuum, but is in Himself for Himself" (Grant, Much Ado Abut Nothing: Theories of Space and Vacuum from the Middle Ages to the Scientific Revolution, p. 218-19).

"…[Guericke's] criticism of Kircher differed somewhat…Kircher believed that even if a void culled exist without a body, which he denied, it could not exist without God. In the passage cited by Guericke, Kircher explained that 'when you imagine this imaginary space beyond the world, do not imagine it as nothing, but conceive it as a fullness of the Divine Substance extended into infinity.' In Guericke's judgment, Kircher was wrong to say that 'God fills all imaginary space, vacuum or emptiness by His substance and presence' and simultaneously deny the existence of empty space. 'For how can God fill what is not' [Experimenta nova, p. 64]. Rather, Kircher ought to have concluded with Lessius that 'imaginary space, vacuum, or the Nothing beyond the world, is God himself,' as he finally does when he announces that the space beyond the world is not Nothing, but is the fullness of Divine Substance.'

"But if space is God's immensity, or even God Himself, Guericke insisted that we must nevertheless understand that 'the infinite essence of God is not contained in space, or vacuum, but is in Himself for Himself" (Grant, Much Ado Abut Nothing: Theories of Space and Vacuum from the Middle Ages to the Scientific Revolution, p. 218-19).

Presuming that your brain, as mine, dissolved into mush during the preceding theologico-philisophico disquisition about nothing, allow me to sum things up: Guericke made something out of nothing, Kircher thought nothing of it, but nothing is divine so let's move on. Don't tell the Know-Nothings, they don't know anything much less nothing.

Someone who, like Guericke, knew something about nothing and possessed it, too, sang about it in 1963, courtesy Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller.

____________

[KIRCHER, Athanasius. SCHOTT, Gaspar]. GUERICKE, Otto von. Experimenta Nova (ut vocantur) Magdeburgica de Vacuo Spatio Primùm à R.P. Gaspare Schotto . . . nunc verò ab ipso Auctore Perfectiùs edita, variisque aliis Experimentis aucta. Quibus accesserunt simul certa quaedam De Aeris Pon Amstelodami [Amsterdam]: Johannes Jansson zu Waesberge, 1672.

First edition. Folio. 8 ff. (including the engraved title), 244, (4) pp., errata leaf. Engraved title, engraved portrait of the author, two double-page engraved plates ((including that of the famous Magdeburg experiment and twenty engravings, many full-page.

Dibner, Heralds of Science, 55 (pp. 30 & 67). Dibner, Founding Fathers of Electrical Science, pp. 13-14. D.S.B., V, pp. 574-76. Evans, Exhibition of First Editions of Epochal Achievements in the History of Science (1934), 30. Horblit 44. Sparrow, Milestones of Science, p. 16.

___________Images courtesy of Martayan Lan, with our thanks.

___________

Another existential brain-twister:

The Story of Nobody, By Somebody, Illustrated By Someone.

___________

___________